File: <russiantickencephalitis.htm> <Medical

Index> <General Index> Site Description Glossary <Navigate

to Home>

|

RUSSIAN TICK ENCEPHALITIS (Contact) Please CLICK on

Image & underlined links for details:

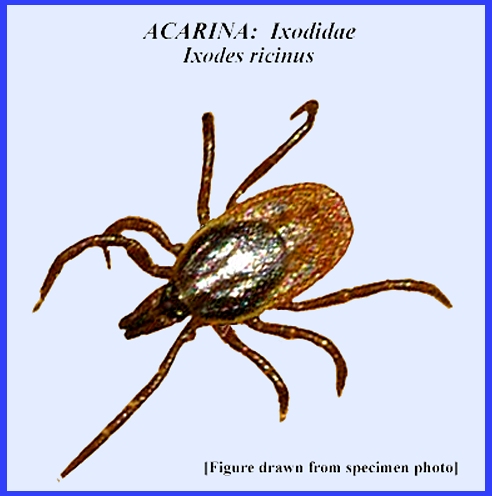

The principal

vector east of Siberia is the tick Ixodes

persulcatus, and in Europe Ixodes ricinus (Service 2008). Other tick species that have been found to

be infected are Dermacentor silvarum,

Haemaphysalis concinna

and H. japonica, but human

transmission is not established. There are two peaks of infection: spring and

summer and ticks are active in a two or three-year cycle. Symptoms are

typically flu-like, and last variable lengths of time depending on the health

of the patient. The virus

multiplies in the tick, migrating to the salivary glands. Human infection occurs from a tick

bite. The ticks themselves, deer,

birds, small rodents and insectivores may be reservoirs for the virus. Service (2008) notes that there is

transstadial and transovarial transmission, but humans are not part of the

natural transmission cycle but only are accidentally infested with

ticks. The virus also resides in the

mammary glands of goats, sheep and cows, whereby humans risk infection by

consuming infected unpasteurized milk or cheese. Russian Tick

Encephalatis - Life Cycle = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = Key References: <medvet.ref.htm> <Hexapoda> Camicas, J. L., J. . Hervy, F. Adam & P. C.

Morel. 1998. The ticks of the world (Acarida,

Ixodida): Nomenclature, Described

Stages, Hosts,

Distribution. Paris: Editions

de l'ORSTOM.. Gammons, M. & G. Salam. 2002. Tick

removal. Amer. Fam. Physician

66: 643-45. Gothe, R., K. Kunze & H. Hoogstraal. 1979.

The mechanisms of pathogenicity in the tick paralyses. J. Med. Ent. 16: 357-69. Hoogstraal, H.

1966. Ticks in relation to

human diseases caused by viruses.

Ann. Rev. Ent. 11: 261-308. Hoogstraal, H.

1967. Ticks in relation to

human diseases caused by Rickettsia

species. Ann. Rev. Ent. 12: 377-420. Legner, E. F. 1995.

Biological control of Diptera of medical and veterinary

importance. J. Vector Ecology 20(1):

59_120. Legner, E. F. 2000.

Biological control of aquatic Diptera. p. 847_870.

Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera, Vol.

1, Science Herald, Budapest. 978 p. Matheson, R. 1950.

Medical Entomology. Comstock

Publ. Co, Inc. 610 p. Needham, G. R. & P. D. Teel. 1991.

Off-host physiological ecology of ixodid ticks. Ann. Rev. Ent. 36: 313-52. Parola, P. & D. Raoult. 2001. Tick-borne

typhuses. IN: The Encyclopedia of arthropod-transmitted

Infections of Man and Domesticated Animals.

ed. M. W. Service, Wallingford: CABI:

pp. 516-24. Service, M.

2008. Medical Entomology For

Students. Cambridge Univ. Press. 289 p Sonenshine, D. E., R. S. Lane & W. L. Nicholson.

2002. Ticks (Ixodida). IN:

Medical & Veterinary Entomology, ed. G. Mullen & L.

Durden,

Ambsterdam Acad. Press.

pp 517-58. Sonenshine, D. E. & T. N. Mather (eds.) 1994.

Ecological Dynamics of Tick-Borne Zoonoses. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. Steer, A., J. Coburn & L. Glickstein. 2005.

Lyme borreliosis. IN: Tick-Borne Diseases of Humans, ed. J. L. Goodman, D. T. Dennis & D. E. Sonenshine. Washington, DC: ASM Press. |