File:

<metamorphosis.htm> < (Entomology), (Invertebrates),

(General Index)> <Invertebrate

Bibliography> <Glossary> <Site Description> < Home>

Introduction Contents►

|

Entomology: METAMORPHOSIS

1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Hexapoda: Class: Insecta: Entomology Metamorphosis (Contact) Please CLICK on underlined

categories to view and on included illustrations to enlarge: Depress Ctrl/F to search for

subject matter: |

|

General

Characteristics of Metamorphosis Insects attain maximum size by

undergoing a succession of molts or ecdyses. The number of molts that an insect

passes through is quite constant for the species, and the form assumed by the

animal between any two ecdyses is called an instar. The animal's existence is thus made up of a

succession of instars (growth) during which the insect is immature, followed

by the attainment of the final adult instar (metamorphosis). In the

simplest and most generalized insects the instars resemble one another and

only differ from the adult in the absence of wings and the incomplete

development of the reproductive system. Where the adult is primitively

wingless, as in silverfish and springtails the change from young to adult is

so slight as to be ignored, and metamorphosis, involving only a development

of the reproductive system, is usually considered to be absent. The insect

orders in this category may be grouped under the Ametabola.

This resting stage is really one

of much physiological and developmental activity, and it is here that many

larval tissues, e.g. the muscles and the alimentary canal, are broken down by

phagocytic or other processes and the new adult tissue is constructed from

many growth centers, usually called imaginal discs. The

change from larva to pupa is often accompanied by a period of inactivity at

the end of the last larval instar. The origin of the phenomenon of holometaboly

is vague. That it is associated with divergent specializations of larvae

and adults in varying degrees is from observation. Therefore, it is not unexpected to find among the orders

composing this group, as, for instance, in many Coleoptera, larvae that are

nymph-like in that they are well cuticularized and have well-developed legs,

and mouthparts resembling those of the adults.

The molting which result is the

route by which either further juvenile stages or the final adult stage can be

attained. In the presence of the secretion of the corpora allata the juvenile

condition results. When these glands

stop functioning, usually at the end of the larval period, the molting

process, still activated by the prothoracic gland, gives rise to the adult. ------------------------------------------- There are four types of metamorphosis (1) Ametabolous, (2)

Paurometabolous, (3) Hemimetabolous and (4) Holometabolous. Ametabolous

Metamorphosis. -- In this type the only

appreciable difference from the immature to the adult is the maturation of

the sex organs (e.g., silverfish) Paurometabolous

Metamorphosis. -- Here the various

mymphs closely resemble the adult except for body proportions. The steps are egg to nymphs to adult

(e.g., grasshopper, milkweed bug). Hemimetabolous

Metamorphosis. -- All the

Hemimetabolaare aquatic. The steps

are egg to naiad to adult. The naiad

is very different from the adult in appearance (e.g., dragonfly, mayfly,

stonefly). The wings are developed externally

in both the hemi- and paurometabolous insects, and these two are often

considered together under the Paurometabola.

The developing wing is called a wingpad. Holometabolous

Metamorphosis. -- Here the steps are

egg to larva to pupa and adult. Wings

are developed internally beneath the cuticula. The pupal is often called the "resting stage," but

this in inaccurate because thee is a complete histolysis of larval tissues

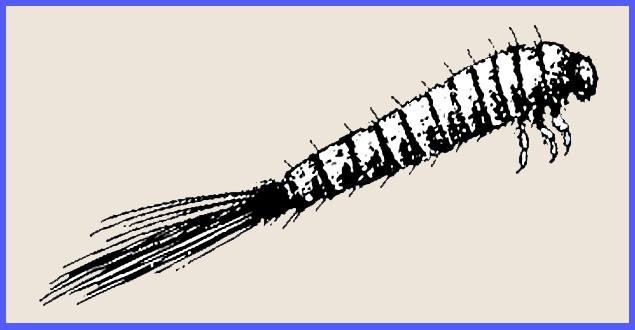

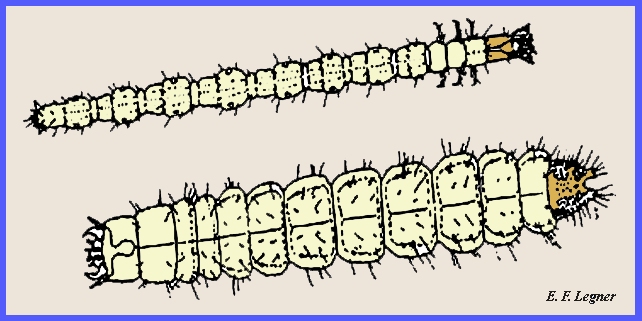

and a reconstruction to the adult. There are five larval types found in the Holometabola: Campodeiform

larvae

are extremely active and

usually predatory. They have a

flattened body with a prognathous head, and their thoracic legs are well

developed for running. Their jaws are

designed for cutting and tearing.

Their cerci and antennae are often well developed (e.g., many beetles,

neuropterans and trichopterans: Fig. ent73).

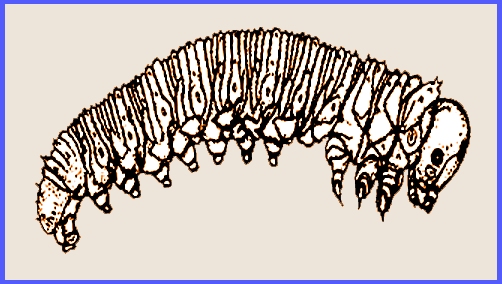

Eruciform larvae are

the opposite of campodeiform by being sluggish, like caterpillars. They have a hypognathous round body. The head is well developed but with very

short antennae, and with thoracic legs and abdominal prolegs (e.g.,

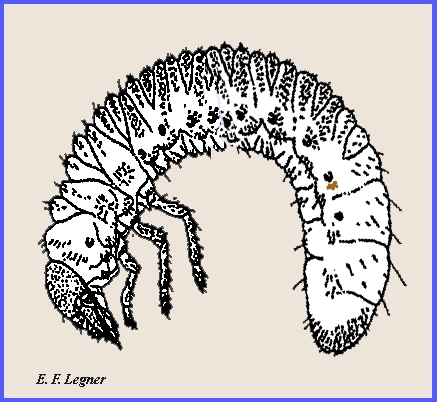

Lepidoptera, Mecoptera and some Hymenoptera: Fig. ent70). Scarabaeiform larvae

inhabit the soil or plant tissues, and some species are enclosed in

tunnels. They are quite helpless

grubs especially when exposed on the surface of the soil. They are hypognathous with a usually

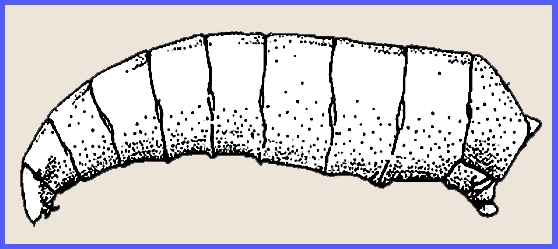

curved body (e.g., June beetle: Fig. ent72). Vermiform

larvae are very advanced with a

reduced head. The body is elongated

and wormlike, legless (e.g., maggots: Fig. ent71). Elateriform larvae are prognathous with a

hard and elongated cylindrical body (e.g., wireworms: Fig. ent74) ------------------------------------------- The adult is the perfect or sexual

stage of an insect. In this stage the

sexual organs mature and locomotory appendages are sufficient for

propagation. The storage of energy varies

considerably among species. Some

adults can only take water or liquid; some adults use fat bodies that were

stored in a previous immature stage, and some, like chironomid midges, cannot

even imbibe liquids. Much of

metamorphosis is directed toward producing an adult that can propagate the

species. Types of Reproduction.

-- Adult insects show various types of reproduction. In oviporous reproduction an egg is

formed and the female lays the egg covered by a chorion. In polyembryony there is a lot of

division in the egg to give many individuals from one egg. In vivipary the insect is born

alive although its origin was still from an egg. In parthenogenesis the young are produced form infertile eggs,

as in aphids. Some species do not

have males, as in the white-fringed beetle.

Some may have a combination of fertile and infertile periods. Paedogenesis involves

reproduction in immature stages. The

maggot young fasten themselves on the parent and consume them. Several generations may pass in this

manner. Egg Shape Variation.

-- The various kinds of sculpturing found on insect eggs are formed by

epithelial cells. Many insects have the means of

fixing their eggs so that they will have a proper environment for

development. Examples are nits, the

eggs of lice, that are glued to the hair of their host and the ovipositor can

cut holes into wood where the eggs are laid.

Lacewings lay their eggs on a stalk, which is a piece of silk with the

egg attached to the end. However,

some insects depend wholly on large numbers of eggs for survival of the

species. Molting

Process. -- The entire cuticle is

cast off and a new one is formed.

This includes lenses of the eyes, mandibles, linings of the fore and

hind guts, tracheal trunks and linings of the genital chamber. Hypodermal cells must lay down the new

cuticula. At the same time the cells

must secrete a fluid, which will erode away much of the endocuticle. This can be resorbed by the hypodermal

cells and used again. When most of

the cuticula has eroded away the insect can molt. New cuticula is very soft and pliable. It remains so for several hours before

being oxidized during which time it can be expanded to accomodate the larger

size of the insect. When the insect

casts its skin, the integument underneath is not pigmented and it remains

white for an hour or more. The instar is

the form of an insect after the molt.

Following egg hatching there can be a first, second and more

molts. The number of instars varies

but it is normally four. Some insects

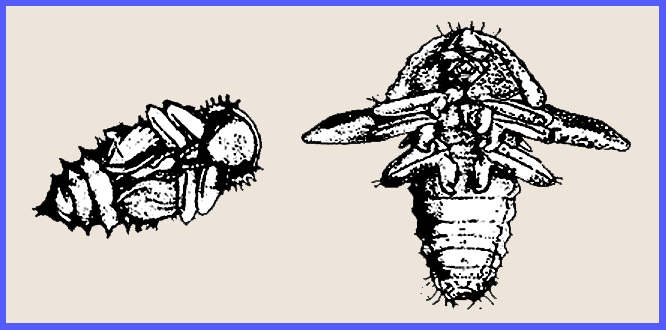

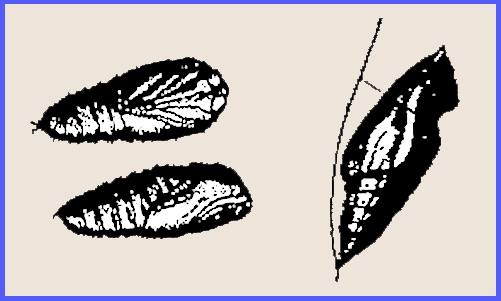

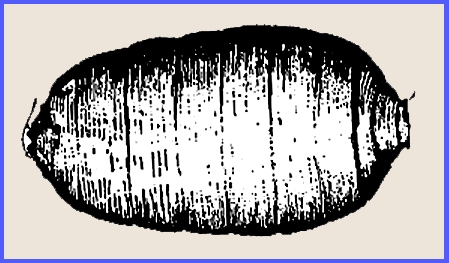

can regress in molting (e.g., carpet beetle). ------------------------------------------- The pupa is an immature stage in

development of the Holometabola. It

is a stage of quiescence primarily even though there can be some movement as

is typical of mosquitoes. It is also

the stage of breakdown of tissue and the buildup of others. Various other names often assigned to this

stage are chrysalis,

puparium and

cocoon. There are three types of pupae: (1) exarate,

where the developing wings, mouthparts and legs are visible externally (e.g.,

Hymenoptera and Coleoptera: Figs. ent75 & ent76). (2) obtect,

where the mouthparts, legs and wings are seen as incompletely formed

structures glued down as an integral part of the pupal case (e.g.,

Lepidoptera: Fig. ent77). (3) coarctate, where an exarate pupa is

formed within the last larval skin.

The exterior is generally smooth and seedlike (e.g., Diptera: Fig. ent78).

============= |

Introduction Contents►