The Weirdness of the World

Chapter One

The weird sisters, hand in hand,

Posters of the sea and land,

Thus do go about, about:

Thrice to thine and thrice to mine

And thrice again, to make up nine.

Peace! the charm’s wound up

(Macbeth,

Act I, scene iii)

Weird often saveth

The undoomed hero if doughty his

valor!

(Beowulf,

X.14-15, trans. L. Hall)

The word “weird” reaches deep back

into old English, originally as a noun for fate or magic, later as an adjective

for the uncanny or peculiar. By the

1980s, it had fruited as the choicest middle-school insult against unstylish kids

like me who spent their free time playing with figurines of wizards and listening

to obscure science fiction radio shows.

If the “normal” is the conventional, ordinary, predictable, and readily

understood, the weird is what defies that.

The world is weird. It wears mismatched thrift-shop clothes,

births wizards and monsters, and all of the old science fiction radio shows are

true. Our changeable, culturally

specific sense of normality is no rigorous index of reality.

One of the

weirdest things about Earth is that certain complex bags of mostly water can

pause to reflect on the most fundamental questions there are. We can philosophize to the limits of our

comprehension and peer into the fog beyond those limits. We can think about the foundations of the

foundations of the foundations, even with no clear method and no great hope of

an answer. In this respect, we vastly out-geek

bluebirds and kangaroos.

1.

What I Will Argue in This Book.

Consider three huge

questions: What is the fundamental structure of the cosmos? How does human consciousness fit into

it? What should we value? What I will argue in this book – with

emphasis on the first two questions, but also sometimes drawing implications

for the third – is (1.) the answers are currently beyond our capacity to know,

and (2.) we do nonetheless know at least this: Whatever the truth is, it’s

weird. Careful reflection will reveal

all of the viable theories on these grand topics to be both bizarre and dubious. In Chapter 3 (“Universal Bizarreness and

Universal Dubiety”), I will call this the Universal Bizarreness thesis and the

Universal Dubiety thesis. Something that

seems almost too crazy to believe must be true, but we can’t resolve which of

the various crazy-seeming options is ultimately correct. If you’ve ever wondered why every wide-ranging,

foundations-minded philosopher in the history of Earth has held bizarre

metaphysical or cosmological views (each philosopher holding, seemingly, a

different set of bizarre views), Chapter 3 offers an explanation.

I will argue that

given our weak epistemic position, our best big-picture cosmology and our best

theories of consciousness are strange, tentative, and modish.

Strange: As I will

argue, every approach to cosmology and consciousness has bizarre implications

that run strikingly contrary to mainstream “common sense”.

Tentative: As I

will also argue, epistemic caution is warranted, partly because theories on these topics run so strikingly contrary to

common sense and also partly because they test the limits of scientific inquiry. Indeed, the nature and value of scientific

inquiry itself rests upon dubious assumptions about the fundamental structure

of mind and world, as I discuss in Chapters 4 (“1% Skepticism”), 5 (“Kant Meets

Cyberpunk”), and 6 (“Experimental Evidence for the Existence of an External

World”).

Modish: On a philosopher’s

time scale – where a few decades ago is “recent” and a few decades hence is

“soon” – we live in a time of change, with cosmological theories and theories

of consciousness rising and receding based mainly on broad promise and what

captures researchers’ imaginations. We ought

not trust that the current range of mainstream academic theories will closely

resemble the range in a hundred years, much less the actual truth.

2.

Varieties of Cosmological Weirdness.

To establish that

the world is cosmologically bizarre, maybe all that is needed is relativity

theory and quantum mechanics.

According to

relativity theory, if your twin accelerates away from you at nearly light speed

then returns, much less time will have passed for the traveler than for you who

stayed here on Earth – the so-called Twin Paradox. According to quantum mechanics, if you

observe the decay of a uranium atom, there’s also an equally real, equally

existing version of you in another “world” who shares your past but who

observed the atom not to have decayed. Or

maybe your act of observation caused the decay, or maybe some other strange

thing is true, depending on your favored interpretation of quantum mechanics. Oddly enough, the many-worlds hypothesis

appears to be the most straightforward interpretation of quantum mechanics. If we accept that view, then the cosmos

contains a myriad of slightly different, equally real worlds each containing

different versions of you and your friends and everything you know, each splitting

off from a common history.

I won’t dwell on

those particular cosmological weirdnesses, since they are familiar to academic

readers and well-handled elsewhere (for example, in recent books by Sean

Carroll and Brian Greene). However, some equally fundamental cosmological

issues are typically addressed by philosophers rather than scientific

cosmologists.

One is the

possibility that the cosmos is nowhere near as large as we ordinarily assume –

perhaps just you and your immediate environment (Chapter 4) or perhaps even

just your own mind and nothing else (Chapter 6). Although these possibilities might not be

likely, they are worth considering

seriously, to assess how confident we ought to be in their falsity and on what

grounds. I will argue that it’s

reasonable not to entirely dismiss

such skeptical possibilities.

Alternatively, and more in line with mainstream physical theory, the

cosmos might be infinite, which brings its own train of bizarre consequences

(Chapter 7, “Almost Everything You Do Causes Almost Everything (Under Certain

Not Wholly Implausible Assumptions); or Infinite Puppetry”).

Another

possibility is that we live inside a simulated reality or a pocket universe,

embedded in a much larger structure about which we know virtually nothing

(Chapters 4 and 5). Still another is

that our experience of three-dimensional spatiality is a product of our own

minds that doesn’t reflect the underlying structure of reality (Chapter 5) or

maps only loosely onto it (Chapter 9, “The Loose Friendship of Visual

Experience and Reality”).

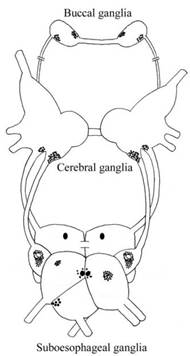

Still another set

of questions concerns the relationship of mind to cosmos. Is conscious experience abundant in the

universe, or does it require the delicate coordination of rare events (Chapter

10, “Is There Something It’s Like to Be a Garden Snail? Or: How Sparse or Abundant Is Consciousness

in the Universe?”)? Is consciousness

purely a matter of having the right physical structure, or might it require

something nonphysical (Chapter 3)? Under

what conditions might a group of organisms give rise to group-level

consciousness (Chapter 2, “If Materialism Is True, the United States Is

Probably Conscious”)? What would it take

to build a conscious machine, if that is possible at all – and what ought we to

do if we don’t know whether we have succeeded (Chapter 11, “The Moral Status of

Future Artificial Intelligence: Doubts and a Dilemma”)?

In each of our

heads are about as many neurons as stars in the galaxy, and each neuron is

arguably more structurally complex than any star system that does not contain

life. There is as much complexity and

mystery inside as out.

I will argue that

in the most fundamental matters of consciousness and cosmology, neither common

sense, nor early 21st-century empirical science, nor armchair philosophical

theorizing is entirely trustworthy. The

rational response is to distribute your credence across a wide range of bizarre

options.

3.

Philosophy That Closes Versus Philosophy That Opens.

You are reading a

philosophy book – voluntarily, let’s suppose. Why? What do you like about philosophy? Some people like philosophy because they

believe it reveals profound, fundamental truths about the one way the world is

and the one right manner to live. Others

like the beauty of grand philosophical systems.

Still others like the clever back-and-forth of philosophical

combat. What I like most is none of

these. I love philosophy best when it

opens my mind – when it reveals ways the world could be, possible approaches to

life, lenses through which I might see and value things around me, which I might

not otherwise have considered.

Philosophy can aim

to open or to close. Suppose you enter

Philosophical Topic X imagining three viable possibilities, A, B, and C. The philosophy of closing aims to reduce the

three to one. It aims to convince you

that possibility A is correct and the others wrong. If it succeeds, you know the truth about

Topic X: A is the answer! In contrast, the

philosophy of opening aims to add new possibilities to the mix – possibilities

that you hadn’t considered before or had considered but too quickly dismissed. Instead of reducing three to one, three grows

to maybe five, with new possibilities D and E.

We can learn by addition as well as subtraction. We can learn that the range of viable possibilities

is broader than we had assumed.

For me, the

greatest philosophical thrill is realizing that something I’d long taken for

granted might not be true, that some “obvious” apparent truth is in fact

doubtable – not just abstractly and hypothetically doubtable, but really,

seriously, in-my-gut doubtable. The

ground shifts beneath me. Where I’d

thought there would be floor, there is instead open space I hadn’t previously seen. My mind spins in new, unfamiliar

directions. I wonder, and wondrousness

seems to coat the world itself. The world

expands, bigger with possibility, more complex, more unfathomable. I feel small and confused, but in a good way.

Let’s test the

boundaries of the best current work in science and philosophy. Let’s launch ourselves at questions

monstrously large and formidable. Let’s

contemplate these questions carefully, with serious scholarly rigor, pushing

against the edge of human knowledge. That

is an intrinsically worthwhile activity, worth some of our time in a society

generous enough to permit us such time, even if the answers elude us.

4.

To Non-Specialists: An Invitation and Apology.

I will try to

write plainly and accessibly enough that most readers who have come this far

can follow me. I think it is both

possible and important for academic philosophy to be comprehensible to

non-specialists. But you should know

also that I am writing primarily for my peers – fellow experts in epistemology,

philosophy of mind, and philosophy of cosmology. There will be slow and difficult patches,

where the details matter. Most of the

chapters are based on articles published in technical philosophy journals –

articles revised, updated, and integrated into what I hope is an intriguing

overall vision. These articles have been

lengthened and deepened, not shortened and simplified. The chapters are designed mostly to stand on

their own, with cross-references to each other.

If you find yourself slogging, please feel free to skip ahead. Trust your sense of what’s interesting to

you.

My middle-school

self who used dice and thrift-shop costumes to imagine astronauts and wizards is

now a fifty-four-year old who uses 21st century science and philosophy to

imagine the shape of the cosmos and the magic of consciousness. Join me!

If doughty our valor, the weird may saveth us.

[Illustration 1 (no caption): a

nerdy middle-schooler in a loose-fitting wizard’s robe, floating on a magic

carpet, against a background of stars and nebulas]

The Weirdness of the World

Part One: Bizarreness and Dubiety

The Weirdness of the World

Chapter Two

I begin with the question of group

consciousness. I start with this issue

because, if I’m right, it’s a quicksand of weirdness. Every angle you pursue, whether pro or con,

has strange implications. The more you

wriggle and thrash, the deeper you sink, with no firm, unweird bottom. In Chapter 3, with this example in mind, I’ll

lay out the broader framework.

For simplicity, I

will assume that you favor materialism

as a cosmological position. According to

materialism, everything in the universe

is composed of, or reducible to, or most fundamentally, material stuff, where

“material stuff” means things like elements of the periodic table and the

various particles or waves or fields that interact with or combine to form such

elements, whatever those particles, waves, or fields might be, as long as they

are not intrinsically mental. Later in the book, I’ll discuss alternatives

to materialism.

If materialism is true, the reason you have a

stream of conscious experience – the reason there’s something it’s like to be

you while there’s nothing it’s like (presumably) to be a bowl of chicken soup,

the reason you possess what Anglophone philosophers call consciousness or phenomenology

or phenomenal consciousness (I use

the terms equivalently)

– is that your basic constituent elements are organized the right way. Conscious experience arises, somehow, from

the interplay of tiny, mindless bits of matter.

Most early 21st century Anglophone philosophers are materialists in this

sense. You might find materialism attractive if you

reject the thought that people are animated by immaterial spirits or possess

immaterial properties.

Here’s another

thought that you will probably reject: The United States is literally, like

you, phenomenally conscious. That is,

the United States literally possesses a stream of experiences over and above

the experiences of its members considered individually. This view stands sharply in tension both with

ordinary common sense opinion in our culture and with the opinion of the vast

majority of philosophers and scientists who have published on the topic.

In this chapter, I

will argue that accepting the materialist idea that you probably like (if

you’re a typical 21st century Anglophone philosopher) should lead you to accept

some ideas about group consciousness that you probably don’t like (if you’re a

typical 21st century Anglophone philosopher), unless you choose instead to

accept some other ideas that you probably ought to like even less.

The argument in

brief is this. If you’re a materialist,

you probably think that rabbits have conscious experiences. And you ought to think that. After all, rabbits are a lot like us,

biologically and neurophysiologically.

If you’re a materialist, you probably also think that conscious

experience would be present in a wide range of naturally evolved alien beings

behaviorally very similar to us even if they are physiologically very

different. And you ought to think

that. After all, it would be

insupportable Earthly chauvinism to deny consciousness to alien species

behaviorally very similar to us, even if they are physiologically

different. But, I will argue, a

materialist who accepts consciousness in hypothetical weirdly formed aliens

ought also to accept consciousness in spatially distributed group entities. If you then also accept rabbit consciousness,

you ought also accept the possibility of consciousness in rather dumb group

entities. Finally, the United States is

a rather dumb group entity of the relevant sort (or maybe even it’s rather

smart, but that’s more than I need for my argument). If we set aside our prejudices against

spatially distributed group entities, we can see that the United States has all

the types of properties that materialists normally regard as indicative of

consciousness.

My claim is

conditional and gappy. If materialism is true, probably the United States is

conscious. Alternatively, if materialism

is true, the most natural thing to

conclude is that the United States is conscious.

1.

Sirian Supersquids, Antarean Antheads, and Your Own Horrible Contiguism.

We are deeply

prejudiced beings. Whites are prejudiced

against Blacks, Gentiles against Jews, overestimators against underestimators. Even when we intellectually reject such

prejudices, they can color our behavior and implicit assumptions. If we ever meet interplanetary travelers

similar to us in overall intelligence and moral character, we will likely be

prejudiced against them too, especially if they look strange.

It’s hard to

imagine a prejudice more deeply ingrained than our prejudice against entities that

are visibly spatially discontinuous – a prejudice built, perhaps, even into the

basic functioning of our visual system. Analogizing to racism, sexism, and

speciesism, let’s call such prejudice contiguism.

You might think

that so-called contiguism is always justified and thus undeserving of a

pejorative label. You might think, for

example, that spatial contiguity is a necessary condition of objecthood or

entityhood, so that it makes no more sense to speak of a spatially

discontinuous entity than it makes sense – barring a very liberal ontology

– to speak of an entity composed of your left shoe, the Eiffel Tower, and the

rings of Saturn. If you’ll excuse me for

saying so, such an attitude is foolish provincialism! The contiguous creatures of Earth are not the

only kinds of creatures there might be. Let

me introduce you to two of my favorite possible alien species.

1.1. Sirian supersquids.

In the oceans of a

planet orbiting Sirius lives a naturally-evolved creature with a central head

and a thousand tentacles. It’s a very

smart creature – as smart, as linguistic, as artistic and creative as human

beings are, though the superficial forms of its language and art differ from

ours. Let’s call these creatures

“supersquids”.

The supersquid’s

brain is not centrally located like our own.

Rather, the supersquid brain is distributed mostly among nodes in its

thousand tentacles, while its head houses digestive and reproductive organs and

the like. However, despite the spatial distribution of

its cognitive processes across its body, the supersquid’s cognition is fully

integrated, and supersquids report having a single, unified stream of conscious

experience. Part of what enables their

cognitive and experiential integration is this: Instead of relatively slow

electrochemical nerves, supersquid nerves are reflective capillaries carrying

light signals, something like Earthly fiber optics. The speed of these signals ensures the tight

temporal synchrony of the cognitive activity shooting among their tentacular

nodes.

Supersquids show

all external signs of consciousness.

They have covertly visited Earth, and one is a linguist who has mastered

English well enough to be indistinguishable from an ordinary English speaker in

verbal tests, including in discussions of consciousness. Like us, the supersquids have communities of

philosophers and psychologists who write eloquently about the metaphysics of

experience, about emotional phenomenology, about their imagery and dreams. Any unbiased alien observer looking at Earth

and looking at the supersquid home planet would see no good grounds for

ascribing consciousness to us but not them.

Some supersquid philosophers doubt that Earthly beings are genuinely

phenomenally conscious, given our radically different physiological

structure. (“What? Chemical

nerves? How protozoan!”) However, I’m glad to report that only a small

minority holds that view.

[Illustration 2

(Caption: A Sirian supersquid philosopher): The supersquid is a nerdy,

intellectual squid with a thousand tentacles (mostly attached but some

detached). Picture it in an underwater

library, reading a (waterproof) book titled “Are Humans Conscious?”. It looks puzzled. Several of its detachable tentacles are

floating around doing various tasks: fetching a book from the shelves, holding

a reading light, writing a letter, carrying a kelp snack, or similar.]

Here’s another

interesting feature of supersquids: They can detach their limbs. To be detachable, a supersquid limb must be

able to maintain homeostasis briefly on its own and suitable light-signal

transceivers must occupy both the surface of the limb and the surface to which

the limb is usually attached. Once the

squids began down this evolutionary path, selective advantages nudged them

farther along, revolutionizing their hunting and foraging. Two major subsequent adaptions were these:

First, the nerve signals between the head and limb-surface transceivers shifted

to wavelengths less readily degraded by water and obstacles. Second, the limb-surface transceivers evolved

the ability to communicate directly among themselves without needing to pass

signals through the head. Since the

speed of light is negligible, supersquids can now detach arbitrarily many limbs

and send them roving widely across the sea with hardly any disruption of their

cognitive processing. The energetic

costs are high, but they supplement their diet and use technological aids.

In this

limb-roving condition, supersquid limbs are not wandering independently under

local limb-only control, then reporting back.

Limb-roving squids remain as cognitively integrated as do contiguous

squids and as intimately in control of their entire spatially-distributed

selves. Despite all the spatial

intermixing of their limbs with those of other supersquids, each individual’s

cognitive processes remain private because each squid’s transceivers employ a

distinctive signature wave pattern. If a

limb is lost, a new limb can be artificially grown and fitted, though losing

too many limbs at once substantially degrades memory and cognitive

function. The supersquids have begun to

experiment with limb exchange and cross-compatible transceiver signals. This has led them toward what human beings

might regard as peculiarly overlap-tolerant views of personal identity, and

they have begun to re-envision the possibilities of marriage, team sports, and

scientific collaboration.

I hope you’ll

agree with me, and with the opinion universal among supersquids, that

supersquids are coherent entities.

Despite their spatial discontinuity, they aren’t mere collections. They are integrated systems that can be

treated as beings of the sort that might house consciousness. And if they might, they do. Or so you should probably say if you’re a

mainline philosophical materialist. After all, supersquids are naturally evolved

beings who act and speak and write and philosophize just like we do.

Does it matter

that this is only science fiction? I

hope you’ll agree that supersquids, or entities relevantly similar, are at

least physically possible. And if such entities are physically possible,

and if the universe is as large as most cosmologists currently think it is –

maybe even infinite, maybe even one among infinitely many infinite universes

– then it might not be a bad bet that some such spatially distributed

intelligences actually exist somewhere. Biology can be provincial, maybe, but not

fundamental metaphysics – not any theory that aims, as ambitious general

theories of consciousness do, to cover the full range of possible cases. You need room for supersquids in your

universal theory of what’s so.

1.2. Antarean antheads.

Among the green

hills and fields of a planet near Antares dwells a species that looks like

woolly mammoths but acts much like human beings. Gazing into my crystal ball, here’s what I

see: Tomorrow, they visit Earth. They

watch our television shows, learn our language, and politely ask to tour our

lands. They are sanitary, friendly,

excellent conversationalists, and well supplied with rare metals for trade, so

they are welcomed across the globe. They

are quirky in a few ways, however. For

example, they think at about one-tenth our speed. This has no overall effect on their

intelligence, but it does test the patience of people unaccustomed to the

Antareans’ slow pace. They also find

some tasks easy that we find difficult and vice versa. They are baffled and amused by our trouble

with simple logic problems like the Wason Selection Task

and tensor calculus, but they are impressed by our skill in integrating

auditory and visual information.

Over time, some

Antareans migrate permanently down from their orbiting ship. Patchy accommodations are made for their size

and speed, and they start to attend our schools and join our corporations. Some achieve political office and display

approximately the normal human range of virtue and vice. Although Antareans don’t reproduce by coitus,

they find some forms of physical contact arousing and have broadly human

attitudes toward love-bonding. Marriage

equality is achieved. What a model of

interplanetary harmony! Ordinary

non-philosophers all agree, of course, that Antareans are conscious.

Here’s why I call

them “antheads”: Their heads and humps contain not neurons but rather ten

million squirming insects, each a fraction of a millimeter across. Each insect has a complete set of tiny

sensory organs and a nervous system of its own, and the antheads’ behavior

arises from complex patterns of interaction among these individually dumb insects. These mammoth creatures are much-evolved

descendants of Antarean ant colonies that evolved in symbiosis with a

brainless, living hive. The interior

insects’ interactions are so informationally efficient that neighboring insects

can respond differentially to the behavioral or chemical effects of other

insects’ individual outgoing efferent nerve impulses. The individual ants vary in size, structure,

sensoria, and mobility. Specialist ants

have various affinities, antagonisms, and predilections, but no ant

individually approaches human intelligence.

No individual ant, for example, has an inkling of Shakespeare despite

the Antareans’ great fondness for Shakespeare’s work.

There seems to be

no reason in principle that such an entity couldn’t execute any computational

function that a human brain could execute or satisfy any high-level functional

description that the human organism could satisfy, according to standard

theories of computation and functional architecture. Every computable input-output relation and

every medium-to-coarse-grained functionally describable relationship that human

beings execute via patterns of neural excitation should be executable by such

an anthead. Nothing about being an

anthead should prevent Antareans from being as clever, creative, and strange as

Earth’s best scientists, comics, and artists, on standard materialist

approaches to cognition.

Maybe there are

little spatial gaps between the ants.

Does it matter? Maybe, in the

privacy of their homes, the ants sometimes disperse from the body, exiting and

entering through the mouth. Does it

matter? Maybe if the exterior body is

badly damaged, the ants recruit a new body from nutrient tanks – and when they

march off to do this, they retain some cognitive coordination, able to remember

and later report thoughts they had mid-transfer. “Oh it’s such a free and airy feeling to be

without a body! And yet it’s a fearful

thing too. It’s good to feel again the

power of limbs and mouth. May this new body

last long and well. Shall we dance,

then, love?”

We humans are not so different perhaps. In one perspective, we ourselves are but

symbiotic aggregates of simpler entities that invested in cooperation.

The Sirian and

Antarean examples establish the following claim well enough, I hope, that most

materialists should accept it: At least some physically possible spatially

scattered entities could reasonably be judged to be coherent entities with a

unified stream of conscious experience.

2.

Dumbing Down and Smarting Up.

You probably think

that rabbits are conscious – that there’s “something it’s like” to be a rabbit,

that rabbits feel pain, have visual experiences, and maybe have feelings like

fear. Some philosophers would deny

rabbit consciousness; more on that later.

For now, I’ll assume you’re on board.

If you accept

rabbit consciousness, you probably ought to accept consciousness in the Sirian

and Antarean equivalents of rabbits.

Consider, for example, the Sirian squidbits, a squidlike species with

approximately the intelligence of rabbits.

When chased by predators, squidbits will sometimes eject their limbs and

hide their central heads. Most Sirians

regard squidbits as conscious entities.

Whatever reasoning justifies attributing consciousness to Earthly

rabbits, parallel reasoning justifies attributing consciousness to Sirian

squidbits. If humans are justified in

attributing consciousness to rabbits due to rabbits’ moderate cognitive and

behavioral sophistication, squidbits have the same types of moderate cognitive

and behavioral sophistication. If,

instead, humans are justified in attributing consciousness to rabbits due to

rabbits’ physiological similarity to us, then supersquids are justified in

attributing consciousness to squidbits due to squidbits’ physiological

similarity to them. Antares, similarly,

hosts antrabbits. If we accept this, we

accept that consciousness can be present in spatially distributed entities that

lack humanlike intelligence, a sophisticated understanding of their own minds,

or linguistic reports of consciousness.

Let me knit together

Sirius, Antares, and Earth: As the squidbit continues to evolve, its central

body shrinks – thus easier to hide – and the limbs gain more independence,

until the primary function of the central body is just reproduction of the

limbs. Earthly entomologists come to

refer to these heads as “queens”. Still

later, squidbits enter into a symbiotic relationship with brainless but mobile

hives, and the thousand bits learn to hide within for safety. These mobile hives look something like woolly

mammoths. Individual fades into group,

then group into individual, with no sharp, principled dividing line. On Earth, too, there is often no sharp,

principled line between individuals and groups, though this is more obvious if

we shed our obsession with vertebrates.

Corals, aspen forests connected at the root, sea sponges, and networks

of lichen and fungi often defy easy answers concerning the number of

individuals. Opposition to group

consciousness is more difficult to sustain if “group” itself is a somewhat

arbitrary classification.

We can also, if we

wish, increase the size of the Antareans and the intelligence of the ants. Maybe Antareans are the size of shopping

malls and filled with naked mole rats.

This wouldn’t seem to affect the argument. Maybe the ants or mole rats could even have

human-level intelligence, while the Antareans’ behavior still emerges in

roughly the same way from the system as a whole. Again, this wouldn’t seem to affect the

argument (though see the Dretske/Kammerer objection in Chapter 2 Appendix,

section 5).

The present view

might seem to conflict with biological (or “type materialist”) views that

equate human consciousness with specific biological processes. I don’t think it needs to conflict, however. Most such views allow that strange alien

species might in principle be conscious, even if constructed rather differently

from us. The experience of pain, for

example, might be constituted by one biological process in us and a different

biological process in a different species.

Alternatively, the experience or “phenomenal character” of pain, in the specific manner it’s felt

by us, might require Earthly neurons, while Antareans have conscious

experiences of schmain, which feels

very different but plays a similar functional role. Still another possibility is that whatever

biological properties ground consciousness, those properties are sufficiently

coarse or abstract that species with very different low-level structures

(neurons vs. light signals vs. squirming bugs) can all equally count as

possessing the required biological properties.

3.

A Telescopic View of the United States.

A planet-sized

alien who squints might see the United States as a single, diffuse entity

consuming bananas and automobiles, wiring up communication systems, touching

the Moon, and regulating its smoggy exhalations – an entity that can be

evaluated for the presence or absence of consciousness.

You might object:

Even if a Sirian supersquid or Antarean anthead is a coherent entity evaluable

for the presence or absence of consciousness, the United States is not such an

entity. For example, it is not a

biological organism. It lacks a life

cycle. It doesn’t reproduce. It’s not an integrated system of biological

materials maintaining homeostasis.

To this concern I

have two replies.

First, it’s not

clear why being conscious should require any of those things. Properly-designed androids, brains in vats,

gods – they aren’t organisms in the standard biological sense, yet they are

sometimes thought to be potential loci of consciousness. (I’m assuming materialism, but some

materialists believe in actual or possible gods.) Having a distinctive mode of reproduction is

often thought to be a central, defining feature of organisms, but it’s not

clear why reproduction should matter to consciousness. Human beings might vastly extend their lives

and cease reproduction, or they might conceivably transform themselves

technologically so that any specific condition on having a biological life cycle

is dispensed with, while our brains and behavior remain largely the same. Would we no longer be conscious? Being composed of cells and organs that share

genetic material might also be characteristic of biological organisms, but as

with reproduction it’s unclear why that should be necessary for consciousness.

Second, it’s not

clear that nations aren’t biological organisms.

The United States is, after

all, composed of cells and organs that share genetic material, to the extent it

is composed of people who are composed of cells and organs and who share

genetic material. The United States

maintains homeostasis. Farmers grow

crops to feed non-farmers, and these nutritional resources are distributed via

truckers on a network of roads. Groups

of people organized as import companies draw in resources from the outside

environment. Medical specialists help

maintain the health of their compatriots.

Soldiers defend against potential threats. Teachers educate future generations. Home builders, textile manufacturers,

telephone companies, mail carriers, rubbish haulers, bankers, judges, all

contribute to the stable well-being of the organism. Politicians and bureaucrats work top-down to

ensure the coordination of certain actions, while other types of coordination

emerge spontaneously from the bottom up, just as in ordinary animals. Viewed telescopically, the United States is

arguably a pretty awesome biological organism. Now, some parts of the United States are also

individually sophisticated and awesome, but that subtracts nothing from the

awesomeness of the U.S. as a whole – no more than we should be less awed by

human biology as we discover increasing evidence of our dependence of

microscopic symbionts.

Nations also

reproduce – not sexually but by fission.

The United States and several other countries are fission products of

Great Britain. In the 1860s, the United

States almost fissioned again. And

fissioning nations retain traits of the parent that enhance the fitness of

future fission products – intergenerationally stable developmental resources,

if you will. As in cellular fission,

there’s a process by which subparts align on different sides and then separate

physically and functionally.

Even if you don’t

accept that the United States is literally a biological organism, you still

probably ought to accept that it has sufficient organization and coherence to

qualify as a concrete though scattered entity of the sort that can be evaluated for the presence or absence of

consciousness. On Earth, at all levels,

from the molecular to the neural to the social, there’s a vast array of

competitive and cooperative pressures; at all levels, there’s a wide range of

actual and possible modes of reproduction, direct and indirect; and all levels

show manifold forms of mutualism, parasitism, partial integration, agonism, and

antagonism. There isn’t as radical a difference in kind

as people are inclined to think between our favorite level of organization and

higher and lower levels.

I’m asking you to

think of the United States as a planet-sized alien might: as a concrete entity

composed of people (and maybe some other things), with boundaries, inputs,

outputs, and behaviors, internally organized and regulated.

We can now ask our

main question: Is this entity conscious? More specifically, does it meet the criteria

that mainstream scientific and philosophical materialists ordinarily regard as

indicative of consciousness?

If those criteria

are applied fairly, without prejudice, it does appear to meet them, as I will

now endeavor to show.

4.

What Is So Special about Brains?

According to

mainstream philosophical and scientific materialist approaches to

consciousness, what’s really special us about is our brains. Brains are what make us conscious. Maybe brains have this power on their own, so

that even a bare brain in an otherwise empty universe would have conscious

experiences if it was structured in the right way; or maybe consciousness

arises not strictly from the brain itself but rather from a thoroughly

entangled mix of brain, body, and environment. But all materialists agree: Brains are

central to the story.

Now what is so

special about brains, on this view? Why

do brains give rise to conscious experience while a similar mix of chemicals in

chicken soup does not? It must be

something about how the materials are organized. Two general features of brain organization

stand out: their complex high order / low entropy information processing, and

their role in coordinating sophisticated responsiveness to environmental stimuli. These two features are of course related. Brains also arise from an evolutionary and

developmental history, within an environmental context, which might play a

constitutive role in determining function and cognitive content. According to a broad class of materialist

views, any system with sophisticated enough information processing and

environmental responsiveness, and perhaps the right kind of historical and

environmental embedding, should have conscious experiences. The central claim of this chapter is: The

United States seems to have what it takes, if standard materialist criteria are

straightforwardly applied without post-hoc noodling. It is mainly unjustified morphological

prejudice that prevents us from seeing this.

Consider, first,

the sheer quantity of information transfer among members of the United

States. The human brain contains about a

hundred billion neurons exchanging information through an average of about a

thousand connections per neuron, firing at peak rates of several hundred times

a second. The United States, in comparison,

has only about three hundred million people.

But those people exchange a lot of information. How much?

We might begin by considering how much information flows from one person

to another by stimulation of the retina.

The human eye contains about a hundred million photoreceptor cells. Most people in the United States spend most

of their time in visual environments that are largely created by the actions of

people (including their past selves). If

we count even one three-hundredth of this visual neuronal stimulation as the

relevant sort of person-to-person information exchange, then the quantity of

visual connectedness among people is similar to the neural connectedness of the

brain (a hundred trillion connections).

Very little of this exchanged information makes it past attentional

filters for further processing, but analogous considerations apply to

information exchange among neurons. Or

here’s another angle: If at any time one three-hundredth of the U.S. population

is viewing internet video at one megabit per second, that’s a transfer rate

among people of a trillion bits per second in this one minor activity alone. Furthermore, it seems unlikely that conscious

experience requires achieving the degree of informational connectedness of the

entire neuronal structure of the human brain.

If mice are conscious, they manage it with under a hundred million

neurons.

A more likely

source of concern, it seems to me, is that the information exchange among the

U.S. population isn’t of the right type

to engender a genuine stream of conscious experience. A simple computer download, even if it

somehow managed to involve a hundred trillion bits per second, presumably

wouldn’t by itself suffice. For

consciousness, presumably there must be some organization of the information in

service of coordinated, goal-directed responsiveness; and maybe, too, there

needs to be some sort of sophisticated self-monitoring.

But the United

States has these properties too. The

population’s information exchange is not in the form of a simply-structured

internet download. The United States is

a goal-directed entity, flexibly self-protecting and self-preserving. The United States responds, intelligently or

semi-intelligently, to opportunities and threats – not less intelligently than

a small mammal. The United States

expanded west as its population grew, developing mines and farms in

traditionally Native American territory.

When Al Qaeda struck New York, the United States responded in a variety

of ways, formally and informally, in many branches of government and in the

population as a whole. Saddam Hussein

shook his sword and the United States invaded Iraq. The U.S. acts in part through its army, and

the army’s movements involve perceptual or quasi-perceptual responses to inputs:

The army moves around the mountain, doesn’t crash into it. Similarly the spy networks of the CIA

detected the location of Osama bin Laden, whom the U.S. then killed. The United States monitors space for

asteroids that might threaten Earth. Is

there less information, less coordination, less intelligence than in a hamster? The Pentagon monitors the actions of the

Army, and its own actions. The Census

Bureau counts residents. The State

Department announces the U.S. position on foreign affairs. The Congress passes a resolution declaring

that Americans hate tyranny and love apple pie.

This is self-representation.

Isn’t it? The United States is

also a social entity, communicating with other entities of its type. It wars against Germany, then reconciles,

then wars again. It threatens and

monitors North Korea. It cooperates with

other nations in threatening and monitoring North Korea. As in other linguistic entities, some of its

internal states are well known and straightforwardly reportable to others (who

just won the Presidential election, the approximate unemployment rate) while

others are not (how many foreign spies have infiltrated the CIA, why the

population consumes more music by Elvis Presley than Ella Fitzgerald).

One might think

that for an entity to have real, intrinsic representations and meaningful

utterances, it must be richly historically embedded in the right kind of

environment. Lightning strikes a swamp

and “Swampman” congeals randomly by freak quantum chance. Swampman might utter sounds that we would be

disposed to interpret as meaning “Wow, this swamp is humid!”, but if he has no

learning history or evolutionary history, some have argued, this utterance

would have no more meaning than a freak occurrence of the same sounds by a random

perturbation of air. But I see no grounds for objection here. The United States is no Swampman. The United States has long been embedded in a

natural and social environment, richly causally connected to the world beyond –

connected in a way that would seem to give meaning to its representations and

functions to its parts.

I am asking you to

think of the United States as a planet-sized alien might, that is, to evaluate

the behaviors and capacities of the United States as a concrete, spatially distributed

entity with people as some or all of its parts – an entity in which people play

roles somewhat analogous to the roles that individual cells play in your

body. If you are willing to jettison

contiguism and other morphological prejudices, this is not, I think, an

intolerably strange perspective. As a

house for consciousness, a rabbit brain is not clearly more sophisticated. I leave it open whether we include objects

like roads and computers as part of the body of the U.S. or instead as part of

its environment.

The

representations and actions of the United States all presumably depend on

what’s going on among the people of the United States. In some sense, arguably, its representations

and actions reduce to, and are nothing but, patterns of activity among its

people and other parts (if any). Yes,

right, and granted! But if materialism

is true, something similar can be said of you.

All of your representations

and actions depend on, reduce to, are analyzable in terms of, and are nothing

but, what’s going on among your parts, for example, your cells. This doesn’t make you non-conscious. As long as these lower-level events hang

together in the right way to contribute to the whole, you’re conscious. Materialism as standardly construed just is

the view on which consciousness arises at a higher level of organization (e.g.,

the person) when lower-level parts (e.g., brain cells) interact in the right

way. Maybe everything ultimately comes

down to and can in principle be fully understood as nothing but the activity of

a few dozen fundamental particles in massively complex interactions. The reducibility of X to Y does not imply the

non-consciousness of X. On standard materialist views, as long as

there are the right functional, behavioral, causal, informational, etc.,

patterns and relationships in X, it detracts not a whit that it can all be

explained in principle by the buzzing about of the smaller-scale stuff Y that

composes X.

I’m not arguing

that the United States has any exotic consciousness juice, or that its behavior

is in principle inexplicable in terms of the behavior of people, or anything

fancy or metaphysically complicated like that.

My argument is really much simpler: There’s something awesomely special

about brains such that they give rise to consciousness, and if we examine the

standard candidate explanations of what makes brains special, the United States

seems to be special in just the same sorts of ways.

What is it about

brains, as hunks of matter, that makes them so amazing? Consider what materialist scientists and

philosophers tend to say in answer: sophisticated information processing,

flexible goal-directed environmental responsiveness, representation,

self-representation, multiply-ordered layers of self-monitoring and

information-seeking self-regulation, rich functional roles, a content-giving

historical embeddedness. The United

States has all those same features. In

fact, it seems to have them to a greater degree than do some entities, like

rabbits, that we ordinarily regard as conscious.

5. Three Ways Out.

Let me briefly

consider three more conservative views about the distribution of consciousness

in the universe, to see if they can provide a suitable exit from the conclusion

that the United States literally has conscious experiences.

5.1. Consciousness isn’t real.

Maybe the United

States isn’t conscious because nobody

is conscious – not you, not me, not rabbits, not aliens. Maybe “consciousness” is a corrupt, broken

concept, embedded in a radically false worldview, and we should discard it

entirely, as we discarded the concepts of demonic possession, the luminiferous

ether, and the fates.

In this chapter,

I’ve tried to use the concept of consciousness in a plain way, unburdened with

dubious commitments like irreducibility, immateriality, or infallible self-knowledge. In Chapter 8, I will further clarify what I

mean by consciousness in this hopefully innocent sense. But let’s allow that I might have

failed. Permit me, then, to rephrase:

Whatever it is in virtue of which human beings and rabbits have

quasi-consciousness or consciousness* (appropriately unburdened with dubious

commitments), the United States has that same thing.

The most visible

philosophical eliminativists about terms from everyday “folk psychology” still

seem to have room in their theories for consciousness, suitably stripped of

objectionable epistemic or metaphysical commitments. So if you take this path, you’re going

farther than they. Denying that

consciousness exists at all seems at least as bizarre as believing that the

United States is conscious.

5.2. Extreme sparseness.

Here’s another way

out: Argue that consciousness is rare, so that really only very specific types

of systems possess it, and then argue that the United States doesn’t meet the

restrictive criteria. If the criteria

are specifically neural, this

position is neurochauvinism, which

I’ll discuss in Section 5.3. Setting

aside neurochauvinism, the most commonly endorsed extreme sparseness view in

one in which language is required for consciousness. Thus, dogs, wild apes, and human infants

aren’t conscious. There’s nothing it’s

like to be such beings, any more than there’s something it’s like (most people

think) to be chicken soup or a fleck of dust.

To a dog, all is dark inside, or rather, not even dark. This view is no less seemingly bizarre than

accepting that the U.S. is conscious.

Like the consciousness-isn’t-real response, it trades one bizarreness

for another. It is no escape from the

quicksand of weirdness. It is also, I

suspect, a serious overestimation of the gulf between us and our nearest

relatives.

Moreover, it’s not

clear that requiring language for consciousness actually delivers the desired

result. The United States does seemingly

speak as a collective entity, as I’ve mentioned. It linguistically threatens and

self-represents, and these threats and self-representations influence the

linguistic and non-linguistic behavior of other nations.

5.3. Neurochauvinism.

A third way out is

to assume that consciousness requires neurons

– neurons bundled together in the right way, communicating by ion channels and

all that, rather than by voice and gesture.

All the entities that we have actually met and that we normally regard

as conscious do have their neurons bundled in that way, and the 3 x 1019

neurons of the United States are not as a whole bundled that way.

Examples from Ned

Block and John Searle lend intuitive support to this view. Suppose we arranged the people of China into

a giant communicative network resembling the functional network instantiated by

the human brain. It would be absurd,

Block says, to regard such an entity as conscious. Similarly, Searle asserts that no arrangement

of beer cans, wire, and windmills, however cleverly structured, could ever host

a genuine stream of conscious experience. According to Block and Searle, what these

entities are lacking isn’t a matter of large-scale functional structure of the

sort that is revealed by input-output relationships, responsiveness to an

external environment, or coarse-grained functional state transitions. Consciousness requires not that, or not only

that. Consciousness requires human

biology.

Or rather,

consciousness on this view requires something like human biology. In what

way like? Here Block and Searle aren’t

very helpful. According to Searle, “any

system capable of causing consciousness must be capable of duplicating the

causal powers of the brain”. In principle, Searle suggests, this could be

achieved by “altogether different” physical mechanisms. But what mechanisms could do this and what

mechanisms could not, Searle makes no attempt to adjudicate, other than by

excluding certain systems, like beer-can systems, as plainly the wrong sort of

thing. Instead, Searle gestures

hopefully toward future science.

The reason for not

insisting strictly on neurons, I suspect, is this: If we’re playing the common

sense game – that is, if bizarreness by the standards of current common sense

is our reason for excluding beer-can systems and organized groups of people –

then we’re going to have to allow the possibility, at least in principle, of

conscious beings from other planets who operate other than by neural systems

like our own. By whatever commonsense or

intuitive standards we judge beer-can systems nonconscious, by those very same

standards, it seems, we would judge at least some hypothetical Martians, with

different internal biology but intelligent-seeming outward behavior, to be

conscious.

From a

cosmological perspective it would be strange to suppose that of all the

possible beings in the universe that are capable of sophisticated,

self-preserving, goal-directed environmental responsiveness, beings that could

presumably be (and in a vast enough universe presumably actually are)

constructed in myriad strange and diverse ways, somehow only we with our

neurons have genuine conscious experience, and all the rest are mere empty

shells, so to speak.

If they’re to

avoid un-Copernican

neuro-fetishism, the question must become, for Block and Searle, what feature of neurons, possibly also

possessed by non-neural systems, gives rise to consciousness? In other words, we’re back with the question

of Section 4: What is so special about brains?

And the only well-developed answers on the near horizon seem to involve

appeals to features that the United States has, like massively complex

informational integration, functional self-monitoring, and a long-standing

history of sophisticated environmental responsiveness.

6. Conclusion.

In sum, the

argument is this. There is no principled

reason to deny psychological properties to spatially distributed beings if they

are sufficiently integrated in other ways.

By this criterion, the United States is at least a candidate for the literal possession of real psychological states,

including consciousness. If we’re

willing to entertain this perspective, the question then becomes whether the

U.S. meets plausible criteria for consciousness, according to the usual

standards of mainstream philosophical and scientific materialism. My suggestion is that if those criteria are

liberal enough to include both small mammals and highly intelligent aliens,

then the United States probably does meet those criteria.

You still have an

objection? I’m unsurprised. Consult the appendix of this chapter where I address

six. This chapter argues for a thesis

that most people are inclined to resist, inspiring the creative construction of

counterarguments.

I would have liked

to strengthen the arguments of this chapter by applying particular, detailed

materialist metaphysical theories to the question at hand, showing how each

does (or does not) imply that the United States is literally conscious. Unfortunately, any attempt to do so presents

four obstacles, in combination nearly insurmountable. First: Few materialist theoreticians

explicitly discuss the plausibility of literal group consciousness. Thus, it’s a matter of speculation how to

properly apply their theory to a case that might have been overlooked in the

theory’s design and presentation. Second:

Many theories, especially those by neuroscientists and psychologists,

implicitly or explicitly limit themselves to human consciousness or at most consciousness in entities with

neural structures like ours, and thus are silent about how consciousness might

work in other types of entities. Third: Further limiting the pool of relevant

theories is the fact that few thinkers really engage the question from top to

bottom, including all of the details that would be relevant to assessing

whether the U.S. would literally be conscious according to their theories. Fourth: When first working through my

thoughts on this topic I arrived at what I thought would be a representative

sample of four prominent, metaphysically ambitious, top-to-bottom theories of

consciousness, it proved rather complex to assess how each view applied to the

case of the U.S. – too complex to tack to the end of an already-long chapter.

Thus, I think

further progress on this issue will require having some specific proposals to

evaluate, that is, some ambitious, general materialist theories of

consciousness that address the question of group consciousness in a serious and

careful way, with enough detail that we can assess the theory’s implications

for specific, real groups like the United States. No theorist has yet, to my knowledge, risen

to the occasion.

Large things are

hard to see properly when you’re in their midst. Too vivid an appreciation of the local

mechanisms overwhelms your view. In the

18th century, Leibniz imagined entering into an enlarged brain and looking

around as if in a mill. You wouldn’t be

inclined, he says, to attribute consciousness to the mechanisms. Leibniz intended this as an argument against

materialism, but the materialist could respond that the scale is misleading. Our intuitions about the mill shouldn’t be

trusted. Parallel reasoning might

explain some of our reluctance to attribute consciousness to the United States. The space between us is an airy synapse.

If the United

States is conscious, is Google? Is an

aircraft carrier? And if such entities are conscious, do they

have rights? I don’t know, but if we

continue down this argumentative path, I expect this will prove quite a mess.

Then get off the

path, you might say! As I see it, we

have four choices.

First: We could

accept that the United States is probably conscious. Maybe this is where our best philosophical

and scientific theories most naturally lead us – and if it seems bizarre or

contrary to common sense, so much the worse for most ordinary people’s

intuitive sense of what is plausible about consciousness.

Second: We could

reject materialism. We could grant that

mainstream materialist theories generate either the result that the United

States is literally conscious or some other implausible seeming result (one of

the various seemingly unattractive ways of escaping that conclusion, discussed

above), and we could treat this as a reason to doubt that whole class of

theories. In Chapters 3 and 5, I’ll

discuss and partially support some alternatives to materialism. However, as I’ll argue there, if you’re drawn

this direction in hopes of escaping bizarreness, that’s futile. You’re doomed.

Third: We could

treat this argument as a challenge to which materialists might rise. The materialist might accept one of the

escapes I mention, such as denying rabbit consciousness (see also Chapter 10),

accepting neurochauvinism, accepting an anti-nesting principle (see section 1

of the appendix to this chapter), or denying that the U.S. is a concrete

entity, and then work to defend that view.

Alternatively, the materialist might devise a new, attractive theory

that avoids all of the difficulties I’ve outlined here. Although this is not at all an unreasonable

strategy, it is unlikely for reasons I’ll explain in Chapter 3 that such a view

will be entirely free of bizarre-seeming implications of one sort or

another. The metaphysics of

consciousness will have weird consequences whichever way you turn.

Fourth: We could

go quietist. We could say so much the worse for

theory. Of course the United States is

not conscious, and of course humans and rabbits are conscious. The rest is speculation, and if that

speculation turns us in circles, well, as Ludwig Wittgenstein suggested,

speculative philosophical theorizing might be more like an illness requiring

cure than an enterprise we should expect to deliver truths.

Oh, how horrible

that fourth reaction is! Take any of the

other three, please. Or take, as I

prefer, some indecisive superposition of those three. But do not tell me that speculating as best

we can about consciousness and the basic structure of the universe is a disease.

1.

Objection 1: Anti-Nesting Principles.

Here’s one way out

of the potentially unappealing conclusion of Chapter 2: Evoke a general

principle according to which a conscious organism cannot have conscious parts –

what I will call an anti-nesting

principle. Anti-nesting says that if

consciousness arises at one level of organization in a system, it cannot also

arise at any smaller or larger levels of organization. We know that we are conscious. It would then follow from anti-nesting that

no larger entity that contains us as parts, like the United States, would also

be conscious.

Anti-nesting

principles have rarely been discussed or evaluated in detail. I am aware of two influential articulations

of general anti-nesting principles in the philosophical and scientific

literature. Both articulations are only

thinly defended, almost stipulative, and both carry consequences approximately

as weird as the group-level consciousness of the United States.

The first is due

to the philosopher Hilary Putnam. In an

influential series of articles in the 1960s, Putnam described and defended a functionalist

theory of the mind, according to which having a mental state is just a matter

of having the right kinds of relationships among states that are definable

functionally, that is, causally or informationally. Crucially, on Putnam’s functionalism, it

doesn’t matter what sorts of material structures implement the functional

relationships. Consciousness arises

whenever the right sorts of causal or informational relationships are present,

whether in human brains, in very differently structured octopus brains, in

computers made of vacuum tubes or integrated circuits, in hypothetical aliens,

or even in ectoplasmic soul stuff.

Roughly speaking, any entity that acts and processes information in a

sophisticated enough way is conscious.

Putnam’s pluralism on this issue was hugely influential, and

functionalism of one stripe or other is probably the standard view about

consciousness in academic philosophy.

It’s an attractive view for those of us who suspect that complex

intelligence is likely to arise more than once in the (probably vast or infinite)

universe and that what matters to consciousness is not its implementation by

neurons but rather the presence of appropriately sophisticated behavior and

informational processing.

Putnam’s

functionalist approach to consciousness is simple and elegant: Any system that has the right sort of

functional structure is conscious, no matter what it’s made of. Or rather – Putnam surprisingly adds – any

system that has the right sort of functional structure is conscious, no matter

what it’s made of unless it is made of

other conscious systems. This is the

sole exception to Putnam’s otherwise liberal attitude about the composition of

conscious entities. A striking

qualification! However, Putnam offers no

argument for this qualification apart from the fact that he wants to rule out

“swarms of bees as single pain-feelers”. Putnam never explains why single-pain-feeling

is impossible for actual swarms of bees, much less why no possible future

evolutionary development of a swarm of conscious bees could ever also be a

single pain-feeler. Putnam embraces a

general anti-nesting principle, but he offers only a brief, off-the-cuff

defense of that principle.

The other

prominent advocate of a general anti-nesting principle is more recent: the

neuroscientist Giulio Tononi (and his collaborators). In a series of articles, Tononi advocates the

view that consciousness arises from the integration of information, with the

amount of consciousness in a system being a complex function of the system’s

informational structure. Tononi’s

theory, Integrated Information Theory (IIT), is influential – though also

subject to a range of, in my judgment, rather serious objections. One aspect of Tononi’s theory, introduced

starting in 2012, is an “Exclusion Postulate” according to which whenever one

informationally integrated system contains another, consciousness occurs only

at the level of organization that integrates the most information. Tononi is thus committed to a general

anti-nesting principle about consciousness.

Tononi’s defense of

the Exclusion Postulate is not much more substantive than Putnam’s defense of

his anti-nesting principle. Perhaps this

is excusable: It’s a “postulate” and postulates are often offered without much

defense, in hopes that they will be retrospectively justified by the long-term

fruits of the larger system of axioms and postulates to which they belong

(compare Euclid’s geometry). While we

await the long-term fruits, though, we can still ask whether the postulate is independently

plausible – and Tononi does have a few brief things to say. First, he says that the Exclusion Postulate

is defensible by Occam’s Razor, the famous principle forbidding us to “multiply

entities beyond necessity”, that is, not to admit more than is strictly

required into our ontology or catalog of what exists. Second, Tononi suggests that it’s unintuitive

to suppose that group consciousness would arise from two people talking. However, no advocate of IIT should rely in

this way on ordinary intuitions about whether small amounts of consciousness

would be present when small amounts of information are integrated: IIT

attributes small amounts of consciousness even to simple logic gates and

photodiodes if they integrate small amounts of information. Why not some low-level consciousness from the

group too? And Occam’s razor is a tricky

implement. Although admitting

unnecessary entities into your ontology seems like a bad idea, what’s an

“entity” and what’s “unnecessary” is often unclear, especially in part-whole

cases. Is a hydrogen atom necessary once

you admit the proton and electron into your ontology? What makes it necessary, or not, to admit the

existence of consciousness in the first place?

It’s obscure why the necessity of attributing consciousness to Antarean

antheads or the United States should depend on whether it’s also necessary to

attribute consciousness to the individual ants or people.

Furthermore,

anti-nesting principles like Putnam’s and Tononi’s, though seemingly designed

to avoid the bizarreness of group consciousness, bring different bizarre

consequences in their train. As Ned

Block argues against Putnam, such principles appear to have the unintuitive

consequence that if ultra-tiny conscious organisms were somehow to become incorporated

into your brain – perhaps, for reasons unknown to you, playing the role of one

neuron or one part of one neuron – you would be rendered nonconscious, even if

all of your behavior and all of your cognitive functioning, including your

reports about your experiences, remained the same. IIT and presumably any other

information-quantity-based anti-nesting principle would also have the further

bizarre consequence that we could all lose consciousness by having the wrong

sort of election or social networking application. Imagine a large election, with many ballot

measures. Organized in the right way,

the amount of integrated information could be arbitrarily large. Tononi’s Exclusion Postulate would then imply

that all of the individual voters would lose consciousness. Furthermore, since “greater than” is a

dichotomous property, there ought on Tononi’s view be an exact point at which

polity-level integration crosses the relevant threshold, causing all

human-level consciousness suddenly to vanish. At this point, the addition of a single vote

would cause every individual voter instantly to lose consciousness – even with

no detectable behavioral or self-report effects, or any loss of integration, at

the level of those individual voters.

It’s odd to suppose that so much, and simultaneously so little, could

depend on the discovery of a single mail-in ballot.

There’s a

fundamental reason that it’s easy to generate unintuitive consequences from

anti-nesting principles, either looking up and out or looking down and in or

both. According to anti-nesting

principles that look up and out, the consciousness of a system depends not

exclusively on what’s going on internally within the system itself but also on

facts about larger structures containing the system, structures potentially so

large as to be beyond the smaller system’s knowledge. Changes in these larger structures could then

potentially add or remove consciousness from the systems within them even with

no internal changes whatsoever to the systems themselves. (This issue will arise again when I discuss

nonlocality in Chapter 3.) According to

anti-nesting principles that look down and in, the consciousness of a system

can depend on structures within it that are potentially so small that they have

no measurable impact on the system’s functioning and remain below its level of

awareness. Such anti-nesting principles

imply the possibility of unintuitive dissociations between what we would

normally think of as organism-level indicators or constituents of consciousness

(such as organism-level cognitive function, brain states, introspective

reports, and behavior) and that organism’s actual consciousness, if those

indicators or constituents happen to embed or be embedded in the wrong sort of

much larger or much smaller things.

I conclude that

neither the existing theoretical literature nor intuitive armchair reflection

support commitment to a general anti-nesting principle.

2.

Objection 2: The U.S. Has Insufficiently Fast and/or Synchronous Cognitive Processing.

Andy Clark has

prominently argued that consciousness requires high-bandwidth neural synchrony

– a type of synchrony that is not currently possible between the external

environment and structures interior to the human brain. Thus, he says, consciousness stays in the

head. Now in the human case, and generally for

Earthly animals with central nervous systems, maybe Clark is right – and maybe

such Earthly animals are all he really has in view. However, we can consider elevating this

principle to a necessity. The

informational integration of the brain is arguably qualitatively different in

its synchrony from the informational integration of the United States. If consciousness, in general, requires

massive, swift, parallel information processing, then maybe mammals are

conscious but the United States is not.

However, this move

has a steep price if we are concerned, as the ambitious general theorist should

be, about hypothetical cases. Suppose we

were to discover that some people, though outwardly very similar to us, or some

alien species, operated with swift but asynchronous serial processing rather

than synchronous parallel processing. A

fast serial system might be very difficult to distinguish from a slower

parallel system, and models of parallel processes are often implemented in

serial systems or systems with far fewer parallel streams. Would we really be justified in thinking that

such entities had no conscious experiences?

Or what if we were to discover a species of long-lived, planet-sized

aliens whose cognitive processes, though operating in parallel, proceeded much

more slowly than ours, on the order of hours rather than milliseconds? If we adopt the liberal spirit that admits

consciousness in Sirian supersquids and Antarean antheads – the most natural

development of the materialist view, I’m inclined to think – it seems we can’t

insist that high-bandwidth neural synchrony is necessary for

consciousness. To justify a more

conservative view on which consciousness requires a particular type of architecture,

we need some principled motivation for denying the consciousness of any

hypothetical entity that lacks that architecture, regardless of how similar

that entity might be in its outward behavior.

No such motivation suggests itself here.

Analogous

considerations will likely trouble most other attempts to deny U.S.

consciousness on broad architectural grounds of this sort.

3.

Objection 3: The U.S. Is So Radically Structurally Different That Our Terms Are

Infelicitous.

Daniel Dennett is

arguably the most prominent living theorist of consciousness. When I was initially drafting the arguments

of this chapter, I emailed him, and he offered a pragmatic objection: To the

extent that the United States is radically unlike human beings, it’s unhelpful

to ascribe consciousness to it. Its behavior is impoverished compared to ours

and its functional architecture is radically unlike our own. Ascribing consciousness to the United States

is not as much straightforwardly false is it is misleading. It invites the reader to too closely

assimilate human architecture and group architecture.

To this objection

I respond, first, that the United States is not behaviorally impoverished. It does many things, as described in Sections

3 and 4 above – probably more than any individual human does. (In this way it differs from the aggregate of

the U.S., Pakistan, and South Africa, and maybe

also from the aggregate of all humanity.) Second, to hang the existence of

consciousness too sensitively on details of architecture runs counter to the